In his Introduction to The Sandman: Endless Nights, Neil Gaiman writes about an encounter he had in a hotel lobby in Turin, where he was asked to tell the story of Sandman in less than 25 words. “I pondered for a moment,” he says, and then he delivers the essence of his highly-regarded series like this: “The Lord of Dreams learns that one must change or die, and makes his decision.”

That’s a powerfully succinct statement, yet filled with thrilling ambiguity, for Gaiman never answers his own implicit question, since while the Morpheus we knew and grew to love does “die,” to be replaced by a new incarnation of the Lord of Dreams, Dream itself never dies. And what does the Sandman choose, anyway? Does he chose to change—and one aspect of his change is his transformation into the Daniel-white-haired-Dream persona with a more sensitive touch? Or does he find himself incapable of change, and that is why “he” dies, only to be reborn as a new version of not-quite-his-old-self?

Gaiman leaves all of that up to the reader to ponder, along with the possibility that the character could have changed and still died. After all, just because the Lord of Dreams learned something doesn’t make it absolutely true in the end.

Only Destiny knows what is inevitable and yet to come.

Throughout this reread, I have been tracking moments when Dream seems to undergo a potential change, looking for signs of which new character inflections reveal that his perspective on life has adjusted his actions in a significant way. Without a doubt, Dream’s 20th century imprisonment changed him, in regard to how he felt about Nada, and her unjust punishment. And the Lord of Dreams risked a great deal to rectify that situation. That was surely a change. And the defiant Dream of the early issues is replaced by the resigned Dream in The Kindly Ones, the creature who has already accepted that he must—and should—fulfill his obligations even when it will lead to his downfall.

But that sense of burden and obligation has been with Dream since our earliest exposure to him. He doesn’t escape his imprisonment only to go free. No, in Preludes and Nocturnes, he escapes Roderick Burgess’s occult dungeon so he can resume his burdensome duties as the Lord of all Dreams. Perhaps he has always been resigned to his station. He is, after all, not really the “king” of the dreamworld—though he plays that role. He’s Dream itself. He’s an idea. Endless.

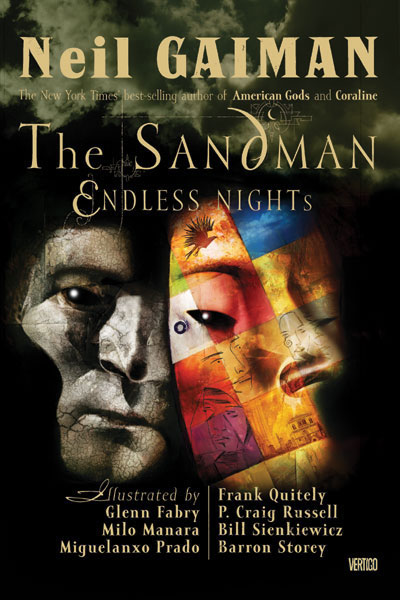

Gaiman’s final contribution to the Sandman saga—until he returns to the character in 2013’s Sandman-in-space miniseries in honor of the 25th anniversary—was a hardcover anthology focusing on Dream and his brothers and sisters. The Sandman: Endless Nights (and note that three letter word that opens the title because this is THE Sandman, not just any old Sandman book) follows a simple structure, as Gaiman and a variety of amazing artistic collaborators tell one short Endless story after another. These aren’t illustrated prose tales in the manner of The Dream Hunters. No, this is Gaiman’s 2003 return to Sandman as a graphic narrative, and he and Team Vertigo wrangled some serious artistic talent to join him.

The first story in the volume, a tale of Death drawn by P. Craig Russell, flashes back and forth through time, as a debaucherous Count has hidden himself and his court from the ravishes of time, and a soldier in the modern day intersects with his story. Gaiman weaves their stories together, but not in the way you might expect. The amateur approach to this kind of story would be to put the Count and the soldier in parallel, or in clear opposition. Gaiman gives them two distinctly separate narrative arcs, all in the space of 24 pages, with Death as the idea that they both share. But it’s not as simple as both accepting or rejecting Death. They have their own motives, but, of course, no matter what they do, Death will be there for them in the end.

Gaiman follows that with a story of Desire, and who better to draw it than that master-of-erotica and modern-and-historical-Romance Milo Manara? Manara’s work here is graceful and appropriately near-pornographic. It’s the story of Desire, after all, and nothing else would quite match the unyielding passions that Endless one constantly evokes. The story features a beautiful woman and the lusts that surround her, but Gaiman gives us a great commentary on the Sandman saga in the midst of the story, as Desire tells the protagonist of this short story about her brother, Dream:

“He talks about stories, my brother,” says Desire. “Let me tell you the plot of every one of his damned stories. Somebody wanted something. That’s the story. Mostly they get it, too.”

Manara draws Desire with an inexpressive, chiseled-but-androgynously-beautiful face as those words are spoken. But the disgust is clear. And so is the irony.

Every story is about somebody wanting something. That’s the nature of story. And that’s what gives Desire its power. But if, in Dream’s stories, they often get what they want, then where does that leave Desire? Of course, Desire comments on that as well: “Getting what you want and being happy are two different things,” she says.

And that, too, is what stories are about. This one included.

The story that follows, “The Heart of a Star,” is a Dream-centric tale drawn by Miguelanxo Prado, an artist who seems to have used watercolors and pastels to create a vivid but delicate depiction of a time long ago.

How long ago?

Well before our solar system was around, in fact, since our sun, Sol, is a character in the story, and he dreams of the kinds of beings that would one day populate his yet-to-be-awakened planets. Sol is a nervous youngster in the story—all glowing and yellow and yet without any confidence in himself—but he’s not the protagonist. No, that honor belongs to Killalla of the Glow, the blue-skinned beauty who can willfully force green flame from her fingertips. She falls in love with the shining green god who is none other than the Light of Oa. And this slice of Green Lantern mythology—as told by Gaiman and Prado—leaves Dream spurned. It was he who brought Killalla to this palace among the stars, and he who introduced her to the sun-beings, and he who is left alone at the end, as others find happiness.

Dream has long been a sad, lonely creature, according to this story.

The Despair and Delirium stories are less affecting, and ultimately less interesting as stories, than most of the others in the volume, even though they are illustrated by the respective talents of Barron Storey and Bill Sienkiewicz. Storey and Sienkiewicz have certain similarities—and surely Sienkiewicz’s early-career transition from his post-Neal Adams style was influenced by Storey’s work (along with that of Gustav Klimt and Ralph Steadman and Sergio Toppi among others)—and they both approach their Endless Nights chapters with furious fragmentation and impressionistic imagery. The Storey installment is titled “Fifteen Portraits of Despair” and there’s no attempt at any kind of panel-to-panel continuity in such a tale, which is, of course, the point. It’s all vicious dagger stabs of ink and paint and horror, with typeset captions discordantly arranged around the pages.

Delirium’s story, “Going Inside,” is closer to a traditional narrative, but only by a degree. It’s chaotic and unsettling, and pushes the reader away with its uncompromising approach to image-making at the expense of direct storytelling.

Both the Despair and Delirium stories are, therefore, exactly appropriate. They are, respectively, painful and unstable. But while the drawings and paintings are profoundly fascinating, they don’t combine with the words to make particularly engaging stories. Evocative, yes. But embedded within this package, also beautifully repulsive.

The effect of reading these stories in sequence, as presented in this volume, is that the fairy-tale like opening trio of tales gives way to the two most challenging and off-putting stories, so when Destruction’s tale comes around—drawn by a “realistic cartoonist” like Glenn Fabry—it seems utterly conventional and disappointingly dull. The Sandman: Endless Nights dares the reader to treat each story on its own terms, but the sequence of the stories in the book provides a series of harsh contrasts. It’s impossible—or it was impossible for me, at least, in this reread—not to measure the stories against one another and as the book unfolds, it becomes increasingly difficult to accept each one as it actually is. They all lie in relation to one another, and so Fabry’s straightforward depiction of a week when Destruction dabbled with an archaeologist becomes a matter-of-fact account of an encounter that seems to lack both the potency of the Death/Desire/Dream fairy tale triumvirate or the jarringly disturbing discordancy of Despair and Delirium. By comparison, Destruction gets a workmanlike story that would have fit better among the issues collected in Fables and Reflections than it does among these more outlandishly exaggerated tellings.

But there’s one more story left to tell, and it’s the story of Destiny, as drawn and painted by Frank Quitely.

The Gaiman and Quitely finale to Endless Nights is the shortest of all the chapters—only eight pages, or a third of the length of most everything else in the volume—and Quitely eschews panels or isolated images in favor of full-page illustrations throughout. His pages may contain inset images, implied movement or “camera” shifts, but they are surrounded not by thick black borders, but rather the seemingly endless void of whiteness. Quitely lets the absence of line and color frame his imagery, and it’s one of the most powerful uses of white space you’ll likely see in comics, and certainly the best example of the technique in the entirety of Sandman.

Quitely’s Destiny story has a softness to it and a particularly surreal dreaminess that’s a fitting way to end the anthology and to provide an implied continuation of the lives of these immortal beings and everything they imply. Destiny’s story is, after all, the greatest story. His book contains all stories, including our own, and in this Gaiman/Quitely short, as Destiny drifts across a landscape filled with gods and humans, life and death, he does not comment on what he reads, he merely observes the pages in front of him. And…“A page turns.”

That was nine years ago, and in that time Neil Gaiman has not written any more Sandman stories, but the legend of the series has continued to grow. There’s a generation of readers who have come to comics at a time when Gaiman’s Sandman has always existed. They haven’t known of a comic book industry in which there was no Sandman, looming large as a masterpiece of the medium. And, for many of these readers, Sandman is a relic of its time. It’s a weird old uncle of a comic book series, too twee in its literary ambitions, perhaps, or too Goth in its trappings, or too much of a nice little bedtime story to be of any lasting value.

But other readers have only come to Sandman recently, as Neil Gaiman has become not “comic book writer Neil Gaiman” but crazy-famous novelist Neil Gaiman, and those readers must surely have a different perspective on the series, as they look at it as a precursor of something else they love. As evidence of a Neil Gaiman yet to be.

Then there are those readers, like me, who were there at the beginning and have taken the time to revisit Gaiman’s Sandman in recent years. I suppose there must be more than a few of us in that situation, for the massive Absolute editions and Annotated Sandman would hardly be appropriate for those who dismiss the series and are unlikely first-time purchases for the uninitiated. Returning to Sandman, reading all of it again, has only reminded me of how vast it can be and yet how vividly specific. It is an artifact from its time, but it’s no relic. It’s not merely of sentimental interest to those of us who frequent the neighborhoods of nostalgia.

Let’s just call Sandman a classic instead.

Tim Callahan enjoyed rereading Sandman more than he expected. And he expected to enjoy it a lot.